The art of adapting a pilgrimage for illness and disability

16

Nov

,

2023

The art of adapting a pilgrimage for illness and disability

By Alice Sainsbury

“The word adventure has gotten overused. For me, when everything goes wrong - that's when adventure starts”

—Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia

Many great journeys start with everything going very wrong and my path has been no exception. Seven years ago I was at the peak of my career as an activewear designer, working with global brands, lecturing and trying in my small way to redefine the status quo of industry ethics and sustainability. Then in December 2015 unbeknown to me, a lesion had started accumulating in my spinal cord. It began demyelinating all of the nerves from my chest down, creating the destructive equivalent of a spinal cord injury. Within twenty-four hours I was paralysed down my left side. After months of being bed bound I began the lengthy journey of physical recovery, learning to live with disabilities, both visible and invisible. It began a process of dealing with the many health complications along the way, demanding acceptance of living with a neurological illness, my new ‘normal’.

“Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.”

―Ralph Waldo Emerson

I felt I had lost much of the purpose to my life and had little reason for carrying on. I had to watch the world moving on without me. But I would also watch the birds swooping, the seasons changing, the elements ebbing and flowing. I liked that nature was moving at the same slow pace as my body. I started to spend more and more time resting outside. It felt safe to be supported by the grass and the elements. The more connected I felt to nature and my new slower way of being the more disillusioned I felt with western societal ideologies. The empty need for vast consumption, the want of the instantaneous, the lack of care for peoples wellbeing and in turn the destruction of our environment. Witnessing our society’s disconnect between the interconnectedness between ourselves and nature felt unbearable. I began deconstructing and reconstructing everything I knew, thought and felt.

The simple act of walking again, immersed in nature, started to become my purpose for each day. Whether it was two steps to the garden on crutches or feeling the first freedom of walking a mile on my own unsupported, a daily walk became not only my daily purpose but a metaphor for regaining my independence and freedom. I felt compelled to keep walking, no matter how slow the journey might be.

So in 2021 I started walking 125 miles of the Cornish Celtic Way. This was a chance to walk through my homelands of Cornwall, to experience all that they had to give from a different perspective. Although I had tried out parts of the trail in groups, I knew I had to do it alone. I told myself at the time that it was a journey of thanks, thanks to all of the charities that had support me through my journey. But there was a deeper reason, I was seeking something that I didn’t yet know.

But what I did know was that this pilgrimage wasn’t going to be a dogmatic challenge or pushing of physical endurance, a narrative that has become sensationalised by a society who organises the body towards acceleration and speed in a world that is rapidly collapsing time and space. This narrative propagates Ego, rather than connection to ourselves and nature through movement. I needed a different narrative.

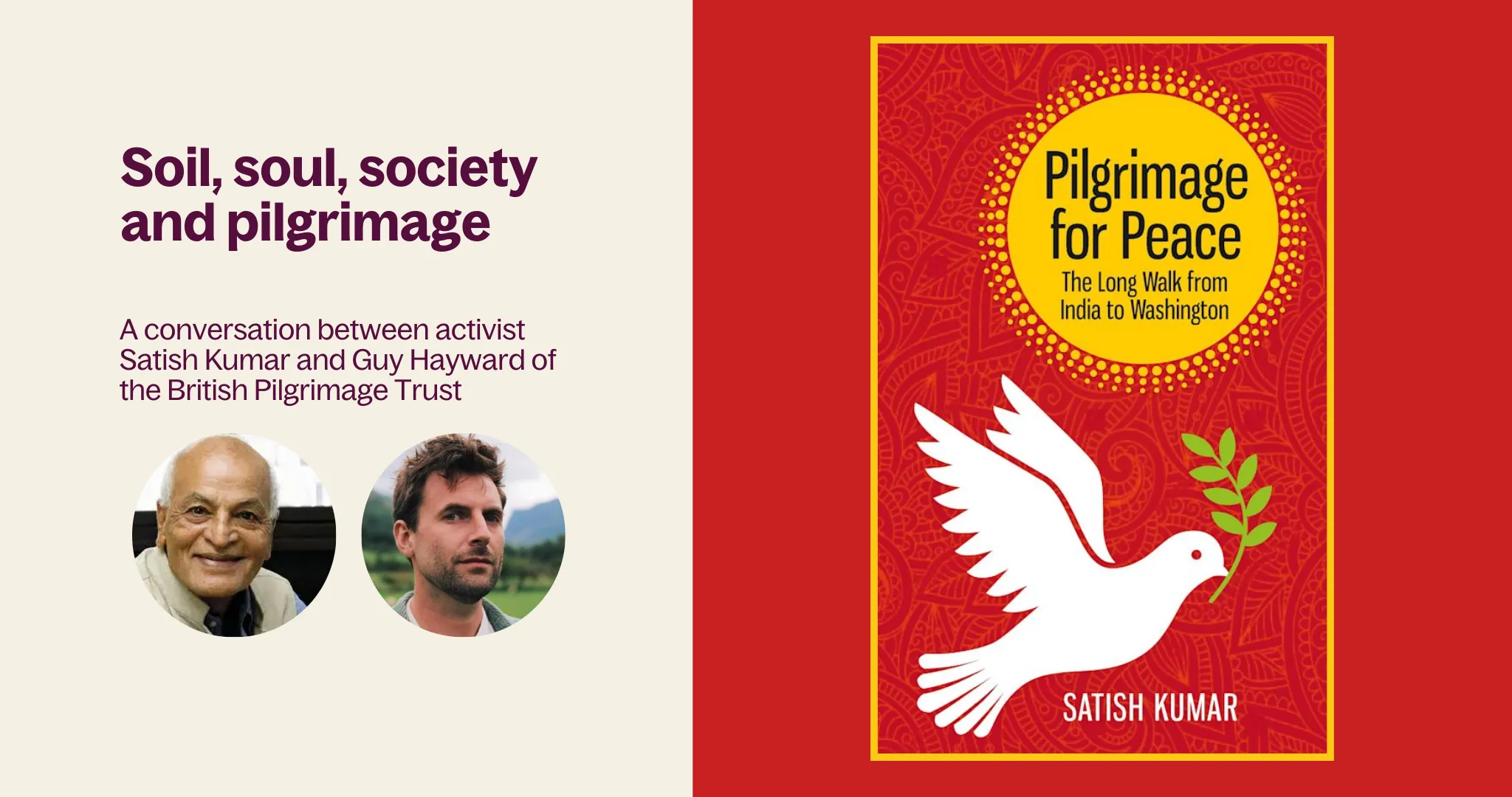

"When you’re walking the destination is not important, the process of walking itself is your journey"

—Satish Kumar

In September 2012, having been blessed by Satish Kumar, and Reverend Nigel Marn’s book as my guide, I set off on my solo journey with my 12kg backpack (my home for the next couple of weeks).

The start of my journey was not as anticipated, it was a beautiful Cornish Indian summer and much hotter than I had expected. However, heat and neurological illness do not always mix, and I found all of my symptoms being exacerbated, both the visible and invisible. With my need to be completely immersed in nature, I had brought everything in that 12kg backpack to camp and be self sustaining on my solo journey. Added to this was my estimation of the distances I had anticipated I would be able to walk each day.

I would soon learn Satish’s lesson of letting go of expectations, as I needed to adapt my thinking. New friends and kind strangers stepped in to carry my bag or move it on to the next campsite for me. I realised I had to halve the distances along the route for each day, and then halved them again, adding in a lot more rest. As I slowed down and surrendered, I started to let go of any expectations.

I would learn that walking this pilgrimage is really about slowing down, and giving time for the paths to naturally unfold in front of you, when you have that time it creates so much space, space to connect to ourselves, our environment, and space to really connect with others whom we may meet along the way.

In life, and particularly in our modern world, living with uncertainty can be hard and the unknown often anxiety inducing. This is especially true in my experience of living with an unpredictable neurological disease, each day filled with worries of being unwell in a social settings, the unknown frustrations of being well enough to cope with the day’s tasks etc. Yet the unknown of each day on the pilgrimage was joyful, the uncertainty of what the day might bring, adventurous. I felt myself opening up, ready and excited for anything the day may bring.

Just as I was opening up along the way, something strange started to happen. Everyone I met along the way, from walkers, to cafe owners, to children were opening up about their own uniques stories of living with different adversities, particularly around illness and disability. This pilgrimage was cultivating a deeper sense of awareness, empathy, compassion and connection, the premise of which would later become the inspiration of the podcast.

"Let your heart be your compass, your mind your map, your soul your guide and you will never get lost.”

—Ritu Ghatourey

Moving at this slower pace was deepening connection in other ways, it was giving time for the paths to naturally unfold and provide space to follow my curiosity, leading to synchronistic encounters and beautiful moments of realisation. These moments and synchronicities would have gone unnoticed or unmet if I had been moving too fast under the premise of ‘challenge’.

I began trusting myself and my body again, letting my senses have free rein, listening to my deeper intuition and allowing it to become my guide through this journey.

The more I listened and followed this inner compass, the more joy I felt, cultivating a deep trust in the path I was on. This deeper trust is what I had been seeking.

That’s not to say the path was always smooth. Inevitably the Cornish weather extremes of rain and mist descended, and I was thankful for the shelter offered by the Churches and halls along the route. Then there was the creeping weakness in my left leg and torso, accompanied by chest pain, (the dreaded TM hug), nausea, dizziness, fatigue, not to mention trying to use catheters in amongst the gorse. I needed more freedom from the physical restraints and neurological pain in my feet, so I thew off my walking boots.

"There is more wisdom in your body than in your deepest philosophy”

—Friedrich Nietzsche

It’s assumed that with a spinal injury and loss of sensation that walking bare foot would lead to injury; but it’s quite the opposite, I felt safer, completely connected to the earth and my body. More able to trust in my movements, determining which sensations are real and which ones are reproduced by the damage in my nervous system. I felt my balance becoming more steady on the trail, and my coordination more attuned. As Asher Clark says ‘Your feet are exactly like your hands, they are made to feel, and they have the same amount of nerve endings. If you cut off that sensory loop, then your brain is not able to make the right choices and movement together’. This trust and connection comes with a sense freedom and relief, which in a body that isn’t always free, this type of connected freedom is the most pleasurable feeling.

“Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better”

—Albert Einstein

Nature has so much to teach us. Living with illness and disability is already a physical, mental and emotional challenge on a daily basis. One that goes unnoticed and un-celebrated living in a society which rarely empathises or supports the very ‘human’ aspect of life through its ideologies, let alone adapts and designs around illness and disability.

Yet nature shows us that there is no ‘normal’. It shows us how to adapt to different seasons, environmental changes, and growth, just as a broken tree will carve a new path, fully supported by the rest of the ecosystem around it.

Accessibility by definition is the practice of making information, activities, and/or environments sensible, meaningful, and usable for as many people as possible.

However understanding what is needed is far more complex without having personal lived experience. With illness and disability each situation and story is so unique and full of different nuances, made more complex by individual experiences ranging from diversity and socio economic factors. I strongly believe it is though hearing, seeing and ultimately gaining true empathy for others personal experiences that we truly gain the deeper levels of understanding needed.

Adapting your pilgrimage:

Everybody has a different reason for undertaking a pilgrimage, whether it be spending time in nature, cultivating a sense of freedom, or connection to deeper spiritual growth. A pilgrimage can really be about slowing down, and giving time for the paths to naturally unfold in front of you, meaning you can adapt your journey and work with your disability or illness, rather than adhering to the common narrative of ‘overcoming’ it. This is a narrative that I have personally struggled with as not only does it denote a level of success (or lack of) for someone living with illness and disability, but it also does not allow for the reality of living with illness and disability.

I realise that I can only speak from my personal experience of adapting a journey around incomplete spinal cord injury and illness, but I hope that the following may help inspire and help guide yours.

You haven’t got to go far from home: gaining a different perspective of your homelands can give you so many new perspectives. This can also be a really helpful place to start as your local knowledge is already going to help in figuring out your logistics. It also means that you are going to be nearer your support system should you need it.

"Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished."

— Lao Tzu

It doesn’t matter how long it takes you or if you can only walk parts at a time. I started the Cornish Celtic Way back in 2021 with two weeks of walking, followed by needing to take over a year out due to needing treatment and an operation. I am still walking the rest in sections and enjoying every part of the journey. Study the guide book or map beforehand, and think about halving the recommended distances and maybe halving these again. Make sure there are lots of rest points.

Add in whole rest days; this is not only important for you physically but will give you a chance to really enjoy new surroundings and engage with sense of place.

What is the terrain like? There may be parts of the route where the terrain is too much or will aggravate symptoms, and you can always adapt your route. Weather conditions may also impact the terrain. It may be that you need to detour along a road or lane, just be sure to take a high visibility jacket for safety.

Support can be really important if you are making your journey solo. Do you have family or friends along the route who might want to join you? Or who might be near by and able to help if needed? My neurological physio was based along the route, so I knew I could always contact them if things got bad physically.

Transport: Is there local transport near by? Collect taxi numbers and bus timetables for the local area you are in. I needed to adapt my thinking around using transport on my pilgrimage. It was’t until I was stuck in Polperro with weakness in my leg, fatigue setting in and the light fading, that I realised I need help the rest of the way and I needed to call a taxi.

When we talk about accessibility, we often only consider the physical and mental barriers, but cost is often a barrier. Most people living with illness and disability are on reduced income, so cost considerations are important, especially with accommodation. I chose to camp so as I could be immersed in nature and enjoy life at a basic simplicity. But thanks to the work of reverend Nigal Marns, all of the churches along the Cornish Celtic Way offered free or very cheap accommodation. See….. for more information.

The right Gear and clothing. Depending on the time of year, what you wear and carry will alter, but always prepare for changing weather. Try out different layering systems, what may be designed for a ‘normal body’ may not work for you, especially if you experience heat regulation issues.

Medical Aid: Always be sure you have your emergency contact(s) stored on your phone, with a description of your condition. You can also wear a medical bracelet. I kept clearly labelled medicines and catheters etc in a dry bag attached to the front of my rucksack for easy access.

Don’t despair when things don’t go to plan, or if you end up lost and not sure if you have taken the right path — this is always part of the journey. Remain open, the right turning my just be a few more steps ahead, the stranger may turn out to be our guide, and adapting our route based on our intuition may lead to the deepest synchronicities.

“When in doubt, just take the next small step”

― Paulo Coelho

About Alice Sainsbury

Based in Cornwall, Alice Sainsbury’s work centres around the art of moving in harmony with ourselves and nature. Breaking down existing narratives and barriers as a specialised consultant in adaptive wear for the outdoors. Whilst also helping others to adapt through the power of somatic exploration, pilgrimage, and conversation that explores these deeper narratives in The Path Unknown podcast. Tao-studio.co

Further reading

.webp)

.svg)

.svg)

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1626228.webp)

Comments

0 Comments

Login or register to join the conversation.

Tom Jones

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Tom Jones

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.